Sports lovers whose tastes lie at the extreme end of the spectrum will be deeply familiar with the Monster Energy brand including the green claw mark (the clawed M icon).

The owner of that iconic brand, Monster Energy Company (MEC), opposed an application by Mixi, Inc. (Mixi) to extend protection to Australia of International Registration 1242961 for the trade mark MONSTER STRIKE in respect of a lengthy list of goods and services summarised as electronic games, gaming and related goods and services. The delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks refused the opposition. MEC appealed this in Monster Energy Company v Mixi Inc [2020] FCA 1398.

MEC opposed the registration of MONSTER STRIKE on the grounds set out in ss 42(b) and 60 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TM Act). S 42(b) allows for opposition on the ground that use of the trade mark in respect of which registration is sought would be contrary to law. MEC held that use of MONSTER STRIKE for electronic games and gaming and related goods and services would have been likely to mislead or deceive consumers. That would contravene ss 18 and 29(1)(g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL). MEC also held that such use of the MONSTER STRIKE trade mark would have been likely to deceive or cause confusion due to the reputation of “certain of its trade marks” in Australia, establishing the ground under s 60. This articles focusses on the s 60 ground of opposition.

Stewart J summarized the “essential question” as whether the use of the MONSTER STRIKE trade mark in relation to electronic games and gaming and related goods and services “would have been likely to mislead or deceive consumers with regard to, or cause consumers to wonder, whether there was any connection in the course of trade between those goods and services and the trader of goods and services that uses MEC’s relevant trade marks.”

S 60 of the TM Act is intended to prevent the registration of a trade mark if there is a likelihood of deception or confusion because of the reputation of a well-known mark in Australia. “Reputation” connotes the “recognition of [the mark] by the public generally” and includes the credit, image and values projected by the trade mark (McCormick & Co Inc v McCormick [2000] FCA 1335). This goes “far beyond mere examination of sales or turnover of goods sold under the trade mark and contemplation of the advertising and promotional figures.” Stewart J appears to refer to “recognition” and “esteem” as two components of “reputation”. The “recognition” component refers to the “quantum of sales, advertising and promotions”. The “esteem” component refers to the credit, image and values projected by the trade mark. Public events and other traders’ marks associated with the mark in question also form the “esteem” component.

In the assessment, the reputation of the other mark must cause the likelihood of deception or confusion to arise. The relevant comparison is between the reputation of the prior mark derived from actual use of that mark, and a notional normal and fair use of the mark sought to be registered in respect of each of the goods or services covered by the specification (Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd v Tivo Inc [2012] FCAFC 159). Also: “The objection under s 60 of the TM Act is not based on the requirement that the allegedly conflicting marks are substantially identical or deceptively similar. The question is purely one of prior reputation.”

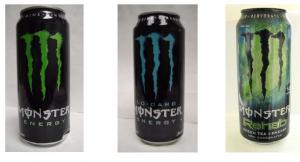

MEC’s 2013 Annual Report was tendered as evidence of reputation. That financial year ended close to the priority date of Mixi’s trade mark application. The report revealed that the MONSTER ENERGY brand drinks represented over 90% of MEC’s sales for 2011, 2012 and 2013. All of the drinks feature one or more of the MONSTER marks on the container. Nearly every can design features the claw mark on the face of the can and then the name: MONSTER (something). The word ENERGY generally appears somewhere close to MONSTER. From 2009 to 2013, more than 78 million cans of Monster energy drinks were sold in Australia, including more than 40 million cans of Monster Energy Original. Here are some examples of the cans:

MEC spends the majority of its advertising, marketing and promotions budget on endorsement of athletes, gamers, musicians and on sponsorship of sporting competitions, eSports competitions and music festivals. MEC and Monster AU spent in excess of US$50 million on marketing and promotional activities in Australia since 2009. US$31.4 million was spent on these activities between 2011 and 2013.

There was no dispute that the MEC trade marks had a strong reputation in Australia at the priority date. That reputation is particularly strong in young men, the identified demographic. Moreover, those marks were clearly identified in relation to MEC’s energy drink known as Monster Energy and its many variants. The evidence was clear that the M icon and the stylised MONSTER almost always appeared one above the other with the word ENERGY in close proximity, on beverage cans. On promotional materials, website pages, social media posts, apparel, promotional vehicles, video games, video game packaging, vehicles, equipment, gear and apparel of sponsored athletes, and on clothing, the M claw is the most prevalent and distinctive of MEC’s Australian marks. Those features were found to make MEC’s products instantly recognisable. Moreover, where there was also wording it was almost always the words MONSTER ENERGY.

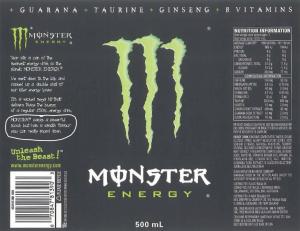

MEC submitted that it also had a reputation in the trade mark MONSTER alone. However, MEC’s submissions identified very few instances of use of MONSTER alone. One example that was tendered is shown below:

The ringed portion is as follows:

The Court did not consider the evidence of such use of MONSTER to have generated any particular reputation for the use of the word MONSTER on its own.

Referring to various other examples of the word MONSTER used on its own by MEC, the Court held that MONSTER is not used as a brand, but rather as a shorthand or abbreviated reference to MONSTER ENERGY, which it identified as “really the brand that has a strong reputation.” According to the Court:

“the evidence does not support a conclusion that the MONSTER word mark on its own had any particularly significant reputation in Australia at the relevant time. Any reputation of the word MONSTER is derived from the M claw, stylised MONSTER and the MONSTER ENERGY word mark. It is these that create the association in the minds of consumers.”

It was only the “device marks incorporating the M icon, the stylised MONSTER and the words MONSTER ENERGY that had a strong reputation in Australia in December 2013.” Furthermore, the reputation was found to be linked to energy drinks.

The Court was not satisfied that there was a “real, tangible danger of a reasonable number of people being caused to wonder whether a trade connection exists between those marks and the MONSTER STRIKE mark if lawfully and normally used in respect of the designated goods and services as at the priority date.” The following cumulative reasons were given:

- The MEC marks had a strong and distinctive reputation that was restricted to energy drinks.

- There are distinctive differences between the relevant marks. The relevant comparison is between the reputation of the opposing marks, on the one hand, and the notional, normal and lawful use of the opposed mark on the other. However, a comparison of the marks themselves is relevant to the inquiry whether there is likely to be confusion. As set out above, there was no particular reputation for MONSTER as opposed to the device marks and the MONSTER ENERGY mark.

- There were about 40 other traders which, at the priority date, had registered or sought to register marks in relation to video and computer games and gaming software that included in their marks the word MONSTER.

- The relevant group of potential customers, being that demographic of young men and women interested in computers, gaming and technology, is generally brand-savvy and not gullible or easily confused. They are not likely on seeing a game or other good or service of the relevant description called MONSTER STRIKE to confuse it with the opposing marks or to be caused to wonder whether the marks are connected.

- There was no evidence of actual confusion between the opposing marks and the MONSTER STRIKE mark, which had been used on about 44 million downloads of the Monster Strike game.

This case emphasises that success with a ground of opposition based on s 60 of the TM Act requires significantly more than just a showing of reputation, regardless of the extent of that reputation. Importantly, it should be shown that the notional group of potential customers or consumers should be confused or caused to wonder whether there is a connection in the course of trade between the marks in question.