It might be an understatement to say that the craft beer market is highly competitive. As the various microbreweries jostle for market position, they are jealous of their branding. And the branding must appeal to a discerning urban palate. Urbanites have long since eschewed the common lager brands that have so long been the stalwart of Australian brewing. And ales have found new favour amongst these urban sophisticates. There are a few forms of ale, including pale ale (which itself can be sub-categorised into the likes of India pale ale and extra pale ale), bright ale, and others.

In the matter of Urban Alley Brewery Pty Ltd v La Sirène Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 82 (7 February 2020), Urban Alley Brewery discovered the importance of careful consideration before changing a brand.

Urban Alley Brewery Pty Ltd (Urban Alley) is the owner of registered trade mark 1775261 covering the plain words “Urban Ale” in class 32 in relation to “Beer” (the “Urban Ale Mark”). The date of filing is 14 June 2016.

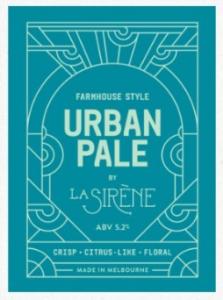

In about October 2016, La Sirène began manufacturing, marketing, offering for sale and selling a beer product with the following label:

Urban Alley commenced proceedings against La Sirène claiming infringement, misleading and deceptive conduct, and the tort of passing off. La Sirène sought an order for the cancellation of the Urban Ale Mark under s88(1)(a) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TMA). Inter alia, La Sirène sought the order on the basis that, under s 41 of the TMA, the mark is not capable of distinguishing Urban Alley’s goods (in respect of which the trade mark is registered) from the goods of other persons. The central issue was the ordinary signification of the words “urban” and “ale” when used in connection with beer and whether the Urban Ale Mark was capable of distinguishing the craft beer product sold by Urban Alley.

Section 41 of the TMA is worth setting out (sans official notes):

(1) An application for the registration of a trade mark must be rejected if the trade mark is not capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is sought to be registered (the designated goods or services) from the goods or services of other persons.

(2) A trade mark is taken not to be capable of distinguishing the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons only if either subsection (3) or (4) applies to the trade mark.

(3) This subsection applies to a trade mark if:

(a) the trade mark is not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons; and

(b) the applicant has not used the trade mark before the filing date in respect of the application to such an extent that the trade mark does in fact distinguish the designated goods or services as being those of the applicant.

(4) This subsection applies to a trade mark if:

(a) the trade mark is, to some extent, but not sufficiently, inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons; and

(b) the trade mark does not and will not distinguish the designated goods or services as being those of the applicant having regard to the combined effect of the following:

(i) the extent to which the trade mark is inherently adapted to distinguish the goods or services from the goods or services of other persons;

(ii) the use, or intended use, of the trade mark by the applicant;

(iii) any other circumstances.

(5) For the purposes of this section, the use of a trade mark by a predecessor in title of an applicant for the registration of the trade mark is taken to be a use of the trade mark by the applicant.

In Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Modena Trading Pty Ltd (2014) 254 CLR 337 (Cantarella), the High Court considered the phrase: “inherently adapted to distinguish”. In that case, the majority endorsed the test formulated by Lord Parker in Registrar of Trade Marks v W & G Du Cros Ltd [1913] AC 624:

Whether other traders are likely, in the ordinary course of their business and without improper motive, to desire to use the same mark, or some mark nearly resembling it, upon or in connection with their own goods.

In Burger King Corporation v Registrar of Trade Marks (1973) 128 CLR 417, Gibb J affirmed previous decisions in holding that assessment commonly calls for an inquiry into the word’s ordinary signification and whether or not it has acquired a secondary meaning. As set out in Cantarella, the consideration of “ordinary signification” is crucial. Such a word would not be an invented word and would have “direct” reference to the character and quality of the goods, or would be laudatory, or a geographical name, or a surname, or had lost distinctiveness or never had the requisite distinctiveness to start with. In Apple Inc. v Registrar of Trade Marks (2014) 227 FCR 522, Yates J. set out:

The notion of inherent adaptation is one that concerns the intrinsic qualities of the mark itself, divorced from the effects or likely effects of registration. Where the mark consists solely of words, attention is directed to whether those words are taken from the common stock of language and, if so, the degree to which those words are, in their ordinary use, descriptive of the goods or services for which registration is sought, and would be used for that purpose by others seeking to supply or provide, without improper motive, such goods or services in the course of trade.

In this case, the parties were in agreement that the word “urban”, when used in connection with beer, conveys, at one level, that the beer is brewed in a city as opposed to a country location. On another level, the word has become associated with craft beer products and breweries, referring to production in inner city locations that are “cool” or “trendy” and attractive for that reason. The parties also agree that the combination of the words “urban ale” does not convey any significance in terms of style or flavour characteristics of beer.

The evidence showed that “urban” had been been used in laudatory way by many journalists. There were many articles published before June 2016 reinforcing the ordinary signification of the word “urban”. There was evidence that a number of businesses had adopted or used the word “urban” in Australia. La Sirène started using “urban” after the filing of the the Urban Ale Mark. But the Court accepted evidence that La Sirène was unaware of the Urban Ale mark. La Sirène chose “urban” because it described the location of its production in an urban area. That was accepted as evidence of adoption of “urban” by a rival trader, without improper motive, as an ordinary signification.

O’Bryan J did not accept Urban Alley’s submission that “urban ale”, when used in connection with beer, is allusive or metaphorical. The evidence showed that the word “urban” had a tangible meaning:

At one level, it describes the beer as having been produced in a city location and, at another level, it connotes that the beer has been produced in an inner-city craft brewery. As such, the use of the word is descriptive and laudatory and the evidence shows that it was commonly used in that manner.

His Honour also did not accept Urban Alley’s submission that the combined words “urban ale” are distinctive. In his view, each of the words “urban” and “ale” are descriptive of beer. Their combination does not alter their ordinary signification or their descriptiveness.

Lessons

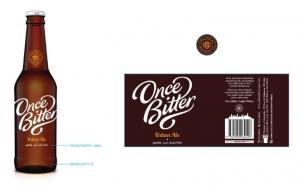

It is instructive to consider that the effective predecessor of the Urban Ale Mark was:

As can be seen “Once Bitter” is given prominence, with “Urban Ale” depicted in a subsidiary manner.

In about mid-2017, a decision was made to stop using “Once Bitter” because it was thought that incorporating the word “bitter” into the label could lead consumers to think that the beer had an “accentuated taste”. An example of the re-branding is:

It is not known whether a trade mark attorney was consulted in this process. However, this would have been an opportunity to select a brand that was unequivocally distinctive. It is easy to regard these things in hindsight, but given the evidence presented, one can assume that the words “urban” and “ale” would have been regarded by a trade mark attorney as possibly lacking in distinctiveness. It is likely that a simple Internet search would have revealed this to be the case. Granted, a trade mark was registered. However, any risk whatsoever of conflict or lack of distinctiveness should be given serious weight at the start of a re-branding project regardless of the opinion of a trade marks examiner.